Hashing: part 2

Part one: Hashing in Java: data structures, collections, security, cryptography

Serialization and hashing

In the first part of the Hashing series, we discussed what hashing means in general and how it is used in Java collections to access stored data in fast way, without unnecessary overhead. In short: computers and software use hashing to compare data quickly. This article will explain the role of hashing in Java serialization process.

But what is serialization?

In object-oriented programming (OOP), we often need to save objects, including composed objects (i.e. objects that contain other objects), to some human-readible form (or at least to some platform-independent, machine-readible form): String, a file (.tmp, .txt and so on), JSON and many others. Once saved, later on, the saved form of file is loaded, then read, and finally the objects are re-created to their initial form for further processing. This processing mirrors some business logic and it is often conducted purely programmatically, through Java code transformation.

Serialization in Java is the process of converting an object’s state into a byte stream, which can be sent over a network or saved to a file for later use. The reverse process of converting the byte stream back into an object is called deserialization. Serialization is important because it allows objects to be easily transmitted across different systems or applications, even if they are written in different programming languages. By converting an object’s state into a byte stream, it becomes platform-independent and can be easily transmitted over a network or saved to a file.

Java supports this general mechanism called serialization, allowing any object to be written to an output stream and to be read again later. In Java, serialization is achieved using the Serializable interface. When a class implements Serializable, it indicates that its instances can be serialized. The Serializable interface is a marker interface that does not contain any methods. Instead, it serves as a signal to the JVM that the class can be serialized. To serialize an object in Java, you can use ObjectOutputStream, which writes the object’s state to a byte stream. To deserialize an object, you can use ObjectInputStream, which reads the byte stream and reconstructs the object.

But what happens when one object is shared by several other objects as part of its state - that is - a common case of composition in object-oriented programming (OOP), frequently referred to as has-a relationship? Serialization and deserialization of plenty of nested objects (with complex hierarchy) is not so trivial. We do not want to have multiple copies of one object serialized. When objects are sharing references to other objects, we need them pointing to some serial number (numeric signature), so that we know to which object they are referring to, without repeating serialization process of that single object and its content.

class Employee {

private long id;

private Department department; // we can have multiple Employees within the same department

private Manager manager; // we can have multiple Employees under the same Manager

// here, Employee with id 1L should point to Manager id 0L, Employee with id 2L should point to Manager id 0L and so on

// Manager 0L should be serialized only once, and Employees should point to its signature (serial number)

}

class Manager {

private long id;

private Department department;

private List<Employee> employees; // one Manager points to multiple Employees

// here, Manager 0L should point to subsequent ids of Employees that he is referring to...

}

During serialization, every object is saved with serial number, hence the name object serialization for this process. When encountering an object reference for the first time, the object and its entire content is saved to the output stream. When encountering the object reference once again, if it has been saved previously, the mechanism makes a kind of annotation: “same as the previously saved object with serial number X, where X is this proper serial number of pre-saved object. When reading back the objects, the procedure is reversed.

Using memory address of a given object as its serial number is useless as it may change - certainly it won’t work for serialization in networking. Memory addresses will vary depending on a machine.

So where the serial number comes from?

It is a hash code counted on the basis of the objects content by SHA algorithm.

First thing: the content. According to Java Object Serialization Specification,

Java object is serialized with default method writeObject() to a file that starts with hexadecimal magic number aced:

aced 0005

0005 is the current version number of the object serialization format.

Every object is saved along with class description. The description contains:

the name of the class

the serial version unique ID, which is a fingerprint of the data field types and method signatures

a set of flags describing the serialization method

a description of the data fields

There is much more interesting information related to low-level serialization mechanism, but let’s leave it for now, and focus on the hashing.

The fingerprint is obtained by ordering the descriptions of the class, superclass, interfaces, field types, and method signatures in a canonical way, and then applying the SHA. This fingerprint is always a 20-byte long (160 bits). However, the serialization mechanism uses only the first eight bytes of the SHA hash code as a class fingerprint, but it is still very likely that when the class data fields or methods changes, the fingerprint also changes.

The versioning problem

Serial number can be viewed by serialver JDK tool from command line:

~/IdeaProjects/blog/assets/java$ serialver HulloDarling

HulloDarling: private static final long serialVersionUID = -6991196364681901587L;

The source file (suppose it’s 1.0 version of an application):

import java.io.Serializable;

public class HulloDarling implements Serializable{

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println("Hullo, darling!");

}

}

But if we change something in the version 1.1 of the application:

public class HulloDarling implements Serializable {

private static final String GREETING = "Hullo, my dear darling!";

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println(GREETING);

}

static String getGreeting() {

return GREETING;

}

}

Serial number will also change:

~/IdeaProjects/blog/assets/java$ serialver HulloDarling

HulloDarling: private static final long serialVersionUID = -4706847282677689375L;

In order to keep compatibility between application versions, so that version 1.1 could deserialize HulloDarling class serialized under version 1.0,

we must add the first (original) serial number manually. In all later versions it should be kept the same for the sake of backward compatibility.

Adding:

private static final long serialVersionUID = -6991196364681901587L;

makes the recent version of HulloDarling has now this serial number instead of automatically generated by SHA (-4706847282677689375L):

~/IdeaProjects/blog/assets/java$ serialver HulloDarling

HulloDarling: private static final long serialVersionUID = -6991196364681901587L;

When a class has a static data member named serialVersionUID , it will not compute the fingerprint automatically (on the basis of the content) but will use that value instead.

It is important to note that hashing in Java serialization does not provide encryption or protection against eavesdropping or interception of the serialized data. It only provides a mechanism to detect if the serialized data has been tampered with or corrupted.

Possible security issue related with deserialization and here

Hashing algorithms

Java uses SHA-1 for serialization, but it is not secure for security-related purposes. Other well-known algorithms are:

- MD5 - introduced by Ron Rives in 1991, it is still used as a checksum (data integrity validation), but it should not be used for cryptographic purposes! MD5 is 128 bits long, and collisions are easily found.

- SHA-2 - it is interesting to note that it was created by the NSA. SHA-2 consists on a few hashing functions: SHA-224, SHA-256, SHA-384, SHA-512, each of them generates digests of given length.

- Blake3 - 256 bits length, not recommended for password hashing. GitHub repo: Blake3

- Argon2

- Whirlpool

- PBKDF2

Use cases

Password verification is one thing. Searching the database for already registered users is another. Hashing is also used to block malicious software, in digital signatures, checksums and cryptocurrencies.

From a privacy point of view, there are scripts that analyse subtle features of the browser and tag a user with some hash. And then they compare it with their database to recognise that web user in other places on the World Wide Web, collecting metadata.

Hashing mechanism can control whether anybody tinkered with original software. Even a slightests change of the content will produce a different value.

Hashing is not about plausibility, authorization nor authentication. It only confirms the identity of the content.

Privacy & security trick:

You can also use a hash to proof a certain piece of information without immediately revealing its content. For example, as a reassurance, a whistleblower report, a secret minute of some very secret meeting that would become not-so-secret afterwards. Maybe you suppose that something in your business can go wrong, but only if it does, you want to publish your statements, not earlier. If not, you wish to keep it secret forever.

How do you solve this?

Save your story in a text file. Generate a hash from the file. Safely store the text file. Transfer the hash to the people that should be informed “in case of”. Do not change anything in the content. If things go wrong, you will provide the same people with your report. The hash is a proof that you drafted your document earlier, so it confirms your version of events.

This strategy was once used by some cybersecurity companies.

Java offers MessageDigest class to generate hashes:

var md = MessageDigest.getInstance("SHA-256");

var hash = md.digest("This String".getBytes(StandardCharsets.UTF_8));

Python has a built-in function to count hash:

python3

Python 3.8.10 (default, Mar 13 2023, 10:26:41)

[GCC 9.4.0] on linux

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> hash("Count a hash value of this String.")

6919382221981311485

>>>

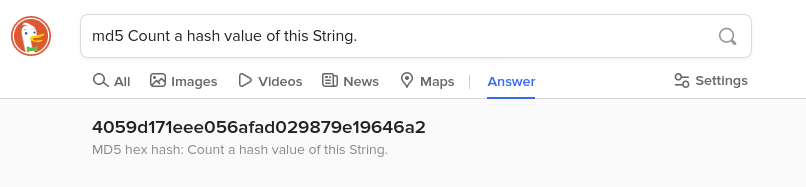

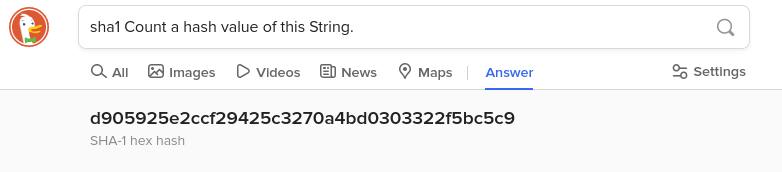

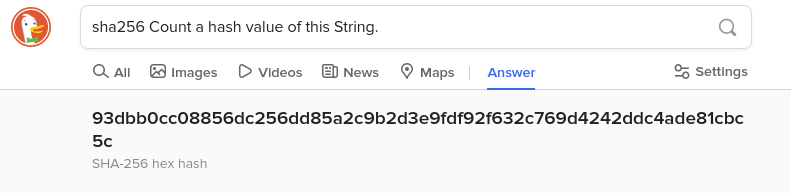

DuckDuckGo browser offers interesting feature:

What about any larger input, like a file? Use terminal commands: md5sum or sha256sum (and the like) in the folder containing given file.

~/IdeaProjects/blog/_backlog$ md5sum to_do

8a62307f50266994aae1b1f6f60f68ee to_do

~/IdeaProjects/blog/_backlog$ sha256sum to_do

43109814f1d5c1c37d409b726cd7e8294e4f27740f59df811c7465c74e755cdb to_do

Veryfiing hash of the file:

md5sum -c <<< "8a62307f50266994aae1b1f6f60f68ee *to_do"

to_do: OK

Remember about the three arrows and the inverted commas. If the filename contains spaces, surround it with single quotation marks. The asterisk can be omitted if you are creating a hash for a text file (as in this case).

Vectors of hashing attacks

Brute forcing

As the same input always generates the same hash digest, brute-forcing might be used to determine what input was the source of a given hash. In theory, all hashing algorithms are vulnerable. In practice, the computational complexity cost of such attack is unreasonably high.

Birthday attack

It consists on so-called birthday paradox. Basically, it is easier to find a colliding input than to discover a real input behind the digest. Meaning, instead of brute forcing a password, it is better to find what makes the same digest. Such input would be used next instead of original one.

DOS (denial of service)

When hashing algorithms makes a lot of collisions, flood of colliding data may affect the performance of a data structure. As a result, a server containing the data is slowed down. It may be crucial in case of security-critical servers handling firewalls, SSH, gateways and the like.

Magic terms and other stuff

- Padding - input data to any cryptographic algorithm are processed one bit at a time (0 or 1), one byte at a time (eight consecutive bits) or by blocks of bytes. If the last block is not complete, the missing bytes are added in one of several well-defined ways (so-called padding).

- Digest length - most common length of hash codes - 128, 160, 256, 384 or 512 bits (16, 20, 32, 48, 64 bytes). The longer the length, the more secure it is (lower probability of collisions), but it may be slower to generate.

- Parity bit (a.k.a. check bit) - A parity bit is a simple error-detection technique used in digital communication systems, such as computer networks and serial communication protocols. It is a single bit that is added to a message to detect errors that may occur during transmission. The parity bit is calculated based on the number of bits in the message that have a value of 1. There are two types of parity: even parity and odd parity. In even parity, the parity bit is set to 1 if the number of 1 bits in the message is odd, and to 0 if the number of 1 bits is even. In odd parity, the parity bit is set to 1 if the number of 1 bits in the message is even, and to 0 if the number of 1 bits is odd. When the message is received, the receiver calculates the parity bit based on the received data and compares it to the parity bit that was transmitted. If the two do not match, an error has occurred during transmission and the receiver can request that the message be retransmitted. Parity bits are a simple and effective way to detect errors in communication, but they do not correct errors. If an error is detected, the message must be retransmitted. More advanced error-detection techniques, such as cyclic redundancy check (CRC), can both detect and correct errors. Parity bit can be considered as the shortest possible digest generated by simplest hashing function.

- Dirichlet’s drawer principle a.k.a. pigeonhole principle mathematically explains duplicates’ occurence and why it is important

- A Bloom filter - an alternative to conventional hashing, space-efficient probabilistic data structure

As the hashing is never-ending matter, the article will be continued and updated, of course.